Featuring "Comme C’est Beau" Vibes for 2026

Also starring "Life Dances On" and "F**k 'Em If They Can't Take a Joke"

Azul fellawen.

Let me begin with the best compliment I’ve received all year:

“I love your style. You look like an Aztec goddess from the future.”

Me:

Delivered at Publix in Miami by a man buying apples. Who then walked away, no lingering, no creepy energy, no expectation, no “now tell me something about me.” Unbothered. That’s the kind of human exchange I can get behind. Just a Masterclass in non-creepy compliments, and a return to the Granny Smiths.

Meanwhile I was wearing loose, floaty linens, not one titty or ass cheek in sight. I told him that the linens were from this incredible brand in Dubai; Sustainably U and to also google Amazigh tattoos and global indigeneity and went back to picking guava pastelitos with my son.

This, I thought, is the kind of exchange I can get behind. Just a human moment. Maybe that’s why it landed so deeply. It was one of the rare times time I felt fully, easily seen, without having to explain context. Just Aztec goddess from the future.

No notes.

Welllllll…..some notes; so gather around.

First of all Amazigh, not Aztec. Bless his heart. He was trying to articulate something he didn’t have the cultural vocabulary for. What he saw was lineage and mythology. What landed was recognition. And to be honest?

Me:

I’ll sit in the future-ancestor energy; I know I look like a walking archive when I wear t-shirts. The Amazigh oucham, these marks that strangers often read as “geometric” or “some cool design” or “Aztec,” in reality belong to a matriarchal cartography older than most nations. But you know colonialism; it’s always confused by the typography and geography and choreography; which brings us to one of my favorite talking points: « « colonialism»»!! Last time this year, I promise.

European colonialism, especially French rule, played a major role in the decline of traditional tribal marking in the Maghreb. It didn’t disappear because it was “Islamic” or “un-Islamic,” but because colonial regimes actively devalued it. They imposed foreign aesthetic standards, undermined local knowledge systems that sustained the practice, and disrupted the social structures; went ahead and broke apart rural communities, women’s circles, intergenerational gatherings, that once ensured its transmission. Forced urbanization, population displacement, the colonial school system: all of it chipped away at the environments and worlds where this knowledge lived.

Under the banner of the so-called mission civilisatrice, Indigenous practices like tattooing were cast as incompatible with modernity. Superstition. Backwardness. The kind of “infamy” Enlightenment thinkers believed had to be crushed. In Algeria and across the Maghreb, Voltaire’s écrasez l’infâme was never just a slogan, it became a governing logic (still continues today with the France banning the headscarf). What couldn’t be translated into the language of reason, hygiene, or progress was marked for erasure. Orientalism added another layer of distortion, turning Amazigh markings into an exoticized, or sexualized, spectacle for Western eyes, stripping it of its spiritual, communal, and identity-rooted meaning.

And because nothing in our history is ever simple, there’s also the element of stigma. As people moved to cities, many feared being shamed or dismissed as “backwards,” little savage nobodies from mountain villages. That anxiety reshaped the gaze. And in that shift, many women began to resent the tattoos they, and their matrilineal heritage, once wore as significant cultural markers. What had been symbols of belonging and beauty became sources of guilt and embarrassment.

For my Muslim homies eager to offer a good naseeha (نصيحة ) a brief historical reminder: the decline of tattooing began in the early 1950s, long after Islam had been in the region for more than a millennium. If Islam itself were the reason, the practice would have disappeared in the 7th century.

What actually changed was the rise of modern Islamic revivalist movements (thanks, Salafis! 🙃) and the social, political, and psychological aftermath of colonial occupation that transformed attitudes toward the practice. Much of what is now framed as “Islamic” opposition to tattooing is less about tradition and more about 20th-century moral reengineering.

And that, I think, is the quiet truth beneath all of this: not every gaze will understand you and not every archive will preserve you so sometimes you have to write yourself back into the frame.

Or, as Yemeni-Egyptian American photographer and filmmaker Yumna Al-Arashi (1988) reminds us: our bodies have always been the archive anyway.

Get her artist book immediately. Al-Arashi traveled through North Africa, where she met and photographed a diverse group of women. By refusing the violence of selection she publishes every single photograph from her journey in this 392 page monograph. The book also includes her prose and poetry in which she reflects on memories of her great-grandmother. It’s the kind of book I would love to someday publish.

And maybe this is why her work feels like the truest mirror to everything I’ve been thinking about since that episode in Publix. Her work refuses the colonial archive that tried to flatten North African women into artifacts or anthropology. In Aisha every single woman is a living record, a reminder that our bodies have been carrying cosmologies long before anyone thought to categorize us. Her photographs honor women whose ink was a language of lineage, not aesthetics; who existed long before the West invented its beauty hierarchies; who never needed to be “legible” to be real.

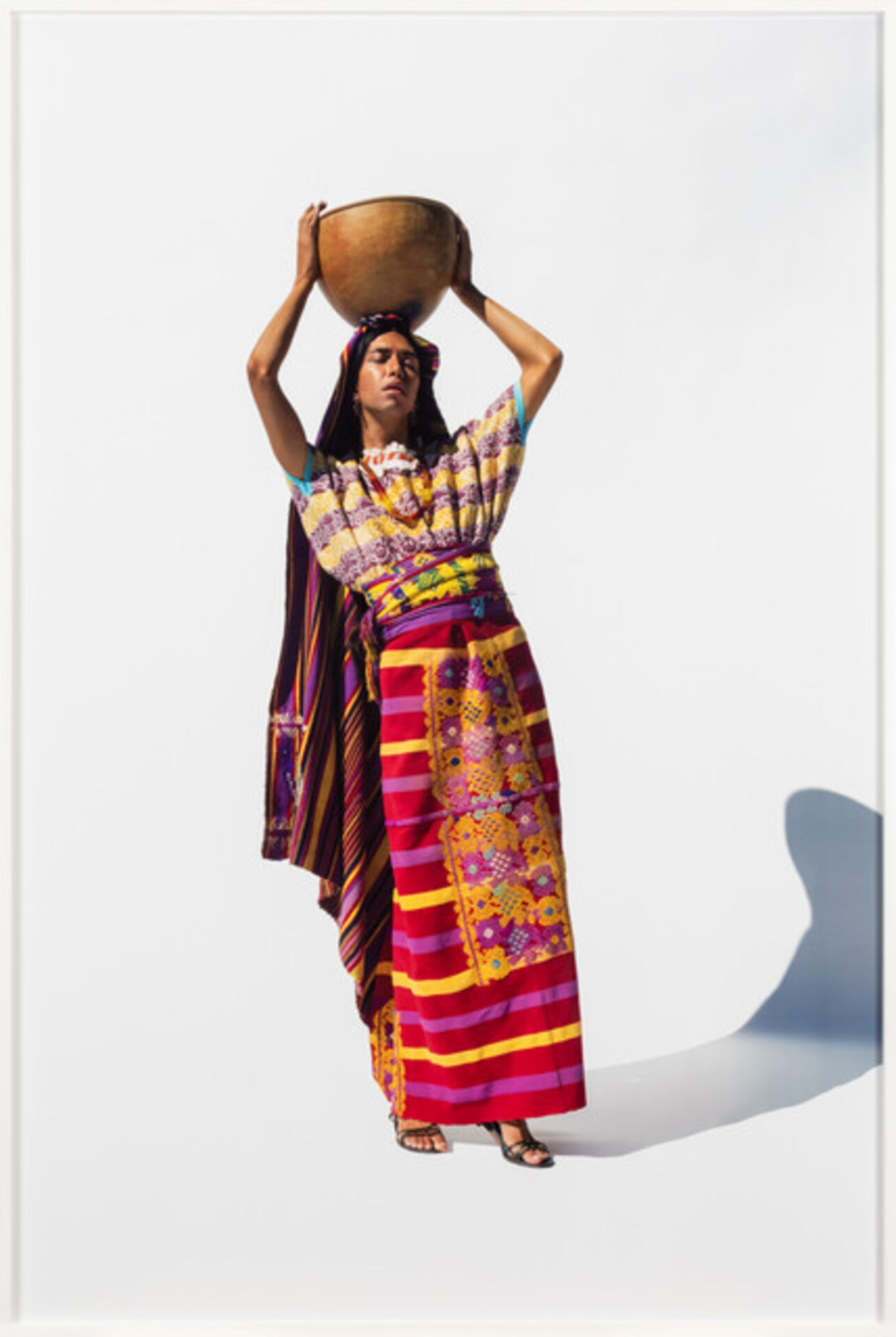

And thinking about being seen without translation, without explanation, reminded me of how artists like Martine Gutierrez have been dismantling the colonial mechanics of desirability for years. In Neo-Indio, Cakchiquel Calor, Gutierrez rejects the tired, extractive gaze that so often flattens Indigenous women into nostalgia or poverty. She stands in full Maya dress, cinta, huipil, corte, styled with the poise of a runway model, yet refusing the Western impulse to treat Indigenous identity as something “past tense.” The garments belonged to her Maya grandmother and Gutierrez stages them not as artifacts but as contemporary power. Across the Indigenous Woman series she plays with the archetype of the supermodel, the West’s most rigid blueprint of desirability, to expose how femininity itself is a performance coded by Whiteness. Her work disrupts the script: who gets seen, who gets desired, who gets flattened, and who gets to write their own image back into the frame.

Her whole approach to the process is “How can we work against the very power structures that propagate beauty and normalcy to the masses?” In other words - how do you serve cunt in a post-imperialist world without reproducing the hierarchies that tried to erase you in the first place?

Multidisciplinary artist Mickalene Thomas also works exactly in the terrain I’m trying to describe; the politics of desirability, who becomes visible, and how society scripts beauty through a Eurocentric lens. Her portraits of Black women deliberately overturn those inherited hierarchies: instead of being flattened, fetishized, or sidelined (as so much of Western art history has done), Thomas places Black women at the center of lush, commanding, rhinestone-studded worlds where they gaze back with full authority. Photography has always been core to her practice, first in self-portraits and intimate photos of her mother, and later of friends and lovers, because it lets her build a counter-archive of Black female presence that refuses white standards of legibility. Drawing on everything from Manet’s nudes to 1970s Black-is-Beautiful imagery and mid-century Black erotica, her work rewrites desire itself, showing Black women as subjects, not objects. Her recent metal photo-collages, layered and hand-embellished, push that idea even further: identity becomes dimensional, fluid, expansive; a reminder that desirability is not a fixed social script but something that can be reclaimed, reframed, and rewritten entirely.

While in Miami, I also attend Art Basel, my professional opinion: yucky.

Hyyperallergic’s Senior Editor Valentina Di Liscia nailed it when she described this year’s Basel as the the Richard Serra problem in reverse. Serra used television to expose the mechanism: you are the product. These works do the opposite: they fold spectators into a revenue stream and call it subversion. Basel isn’t embracing digital art because it discovered radical ideology; it’s filling economic gaps left by galleries that withdrew. No one has money. Crypto shows up as both spectacle and capital. I’ve always moved quietly. I’m deeply uncomfortable with social media and the endless performance of the online self; being sold something doesn’t bother me nearly as much as being mined for data. I’m not claiming moral purity, I love a thingie, my aesthetic is basically heritage maximalism, it’s just not how I want to exist. I’d rather opt out than pretend participation equals liberation.

But in genuinely good news, Saudi multidisciplinary artist Mohammad Alfaraj, won the 2025 Art Basel Gold Award for Emerging Artists. I shouldn’t care about Euro-centric institutional awards like this, but the truth is I do, because in the real world, they matter.

The numbers are brutal. 83% of collectors are in the U.S. and Europe. Half of all galleries are concentrated in just three countries: the U.S. (34%), Germany (12%), and the UK (10%). Over 20% of galleries sit in only five cities: New York, London, Berlin, Paris, Los Angeles. One study found that only 0.05% of artists who start in low-prestige venues ever make it into the top tier. If you don’t circulate through these hubs, you’re invisible. Sorry, babes.

So yes, an award from Basel matters. It feeds the algorithm of legitimacy, circulation, invitations, funding, visibility. It’s not the world we want, but it’s the world we’re in. So let’s play. The house wins, anyway.

Alfaraj has been quietly building his own cosmology for years, humans, animals, imagined beings sharing the same universe. And then he walks up to receive the award in a thobe, shemagh, and agal in Miami Beach. يا هلاااا 🧿

Also before coming down to Miami, in D.C., I saw The Stars We Do Not See at the National Gallery of Art. Sebastian Smee wasn’t wrong - the work is powerful. Aboriginal artists carry entire cosmologies in their hands (you can see I’m in a cosmology kind of mind recently). But the exhibition felt like someone dumped everything into one room and hoped meaning would self-organize or the audience would make meaning from the chaos. That familiar spectacle of inclusion: how many artists, how many nations, how many mediums. Breadth becomes a shield against critique.

I’ve seen this before. Brilliant artists, messy institutions. “Inclusive” instead of intentional. Quantity ≠ coherence. The strongest works get swallowed.

Professional opinion: pure headassery.

This is the same old problem: homogenization. One exhibition asked to represent entire peoples. Centuries flattened into themes: earth, ancestors, ritual. Decolonizing language, recolonizing structure. The art deserves better. The curation rarely rises to meet it.

Anyway.

For 2026, try being vaguely solar-powered. Make no resolutions. See women through less patriarchal eyes: deadly, mythic, radiant; possibly descended from volcano goddesses. Also dance to this:

Most importantly, mind your business.

Happy end of 2025. Next year I’m aiming for laughter and money and clarity and forward motion; all of it; less interested in being palatable and more interested in serving cunty with intention.

All my love, as always. See you next time.

Wided

x